Volume 12, Issue 3 (September 2025)

Avicenna J Neuro Psycho Physiology 2025, 12(3): 149-155 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: IR.YAZD.REC.1399.016

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Sotoudeh M, Rezapour Mirsaleh Y, Choobfroushzadeh A. Mediating Role of Self-compassion in the Relationship Between Attachment Styles and Mental Rumination in Infertile Women. Avicenna J Neuro Psycho Physiology 2025; 12 (3) :149-155

URL: http://ajnpp.umsha.ac.ir/article-1-544-en.html

URL: http://ajnpp.umsha.ac.ir/article-1-544-en.html

1- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran ,y.rezapour@ardakan.ac.ir

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran

2- Department of Counseling, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran ,

3- Department of Psychology, Faculty of Humanities & Social Sciences, Ardakan University, Ardakan, Iran

Full-Text [PDF 354 kb]

(51 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (556 Views)

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations among the variables

Full-Text: (67 Views)

Background

Infertility is a deeply distressing experience, particularly for women, often accompanied by feelings of shame, self-blame, and social withdrawal. Some women refrain from discussing infertility with family or friends for fear of reproach, which can exacerbate emotional distress and harm both marital and social relationships. In coping with infertility, women employ both adaptive and maladaptive strategies, among which we can refer to mental rumination—a repetitive, negative pattern of thinking about one’s distress and perceived failures [1]. Mental rumination prolongs depression and emotional suffering, trapping individuals in a cycle of negative thoughts that impair problem-solving and emotional regulation [2]. In infertile women, it can heighten anxiety, affect health, strain relationships, and create insecurity about the future [3]. On the contrary, self-compassion, defined as the ability to treat oneself with kindness, recognize shared human suffering, and remain mindful of distress, can buffer these effects [4]. Self-compassion helps reduce stress, anxiety, and self-criticism while fostering emotional balance and resilience. It has been demonstrated to mitigate shame and stress among infertile women [5] and improve emotional regulation during infertility treatment [6].

Attachment style—a key factor in emotional coping—also plays a critical role in infertility adjustment. Based on attachment theory, early relationships with caregivers shape how individuals interact with others in adulthood [7]. Adults with secure attachment typically possess self-worth, trust in others, and the capacity for intimacy, while those with insecure avoidant or ambivalent attachment styles may struggle with trust, fear of intimacy, and emotional instability [8]. These differences affect how infertile women experience and express distress. Securely attached women are more likely to seek and accept spousal support, enhancing marital satisfaction and emotional stability [9]. On the contrary, insecurely attached women may conceal their infertility due to fear of judgment or dependency, which exacerbates their psychological distress.

There is substantial evidence that attachment styles are associated with self-compassion and mental health. Research suggests that secure attachment fosters self-compassion and psychological resilience [10], whereas insecure attachment is linked to self-criticism, rumination, and reduced emotional well-being [11]. Considering the aforementioned points, attachment styles are confirmed to have a marked impact on self-compassion, which serves as an effective strategy for managing emotions in pregnancy [12]. Securely attached individuals—having received consistent care and validation—tend to internalize warmth and understanding, while those with inconsistent or neglectful caregivers often struggle to extend compassion to themselves. Consequently, self-compassion functions as a crucial mediator between attachment styles and emotional outcomes, such as mental rumination [13]. Based on these findings, it is proposed that attachment style significantly influences both self-compassion and infertility-related mental rumination. Secure attachment may serve as a protective factor, mitigating ruminative thinking through enhanced self-compassion, while insecure attachment increases vulnerability to negative self-reflection and emotional distress. Therefore, fostering self-compassion could be a valuable therapeutic approach to help infertile women manage their emotions, reduce maladaptive rumination, and improve their psychological well-being.

Objectives

Infertility causes significant psychological, social, and financial distress for women, often leading to reduced quality of life and self-blame. The enhancement of self-compassion may alleviate these difficulties, helping women value themselves beyond childbearing and improving treatment outcomes. In light of the aforementioned issues, the present study evaluates the relationships among attachment styles, self-compassion, and mental rumination to support the proposed model. If confirmed, targeted interventions aimed at the mitigation of rumination in infertile women can be developed with greater confidence.

Materials and Methods

Research Design and Participants

This cross-sectional correlational study employed structural equation analysis. The research population consisted of all primary infertile women referring to fertility centers of Yazd, Fars, Kerman, and Isfahan provinces in Iran in 2020. They were clinically diagnosed with infertility. A total of 346 women were selected via the available sampling method. The inclusion criteria entailed passing at least three years of married life, a tendency to have children, primary infertility, a continual treatment period of at least one year after infertility diagnosis, and the age range of 20-40 years. On the other hand, participants with infertility-related physical disorders, psychiatric disorders, and a history of using psychiatric medications were excluded from the study. The candidates’ compliance with the inclusion criteria was assessed by the interviews conducted with them and reviews of their medical history.

Measures

Adult Attachment Inventory (AAI): The Persian version of the adult attachment scale was designed based on Hazan and Shaver’s questionnaire. The validity and reliability of this scale were confirmed among Tehran University students [14]. The AAI includes 15 items that assess the secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent styles of attachment based on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for these three styles were found to be 0.86, 0.84, and 0.85, respectively (0.86, 0.83, and 0.84 for females and 0.84, 0.85, and 0.86 for males). The convergent and discriminant validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability of AAI were confirmed. The test-retest reliability for secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent were reported as 0.82, 0.78, and 0.75, respectively [14].

Self-compassion scale (SCS): This 26-item questionnaire encompasses six subscales of self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification [4]. The items are scored based on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The alpha coefficients of the Persian version of SCS were reported as 0.91, 0.77, 0.70, 0.72, 0.72, 0.68, and 0.67 for total items, self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification subscales, respectively [15]. The factor structure of the Persian version of SCS in an Iranian sample was confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis [15]. The content validity index and content validity ratio of the Persian version of SCS were obtained as 0.82-0.95 and 0.78-0.95 [16].

Ruminative response scale (RRS): The RRS contains 22 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The total score ranged from 22 to 88, with higher scores suggesting higher levels of mental rumination [17]. The Cronbach's alpha and test-retest reliability coefficient of RRS were 0.88-0.92 and 0.67 (Luminet, 2003). The Cronbach’s alpha for the Persian version of RRS was 0.88 in a sample of Iranian students. The Persian version of the RRS has a significant positive correlation with anxiety and depression [18]. The factor structure of the Persian version of the RRS was confirmed, and the test-retest reliability was 0.67 [19].

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling and Pearson correlations were used to assess variable relationships using SPSS and AMOS software packages (version 16). The missing data were replaced with participants’ responses within the same domain. Significance was set at P<0.05. The assumptions for structural equation analysis, including nonlinearity (via variance inflation and tolerance tests), independence of errors (Durbin-Watson test), and linearity (scatter plots), were tested. Indirect effects were analyzed using the bootstrapping technique.

Results

The mean age of participants was 28.56±3.93 years, respectively. All the participants had the experience of one marriage. The immediate relatives of 229 participants (66.2%) had no infertility history; nonetheless, the case was positive for the other 117 (33.8%) participants. Moreover, 30, 103, 114, and 99 subjects had been married for less than 3, 3-6, 7-9, and more than 9 years, respectively. Regarding infertility treatment, 51 cases were making their first attempt to treat infertility, 51 others had a previous failed attempt, 131 had 2-4 failed attempts, and 111 had more than four failed attempts to treat their infertility. The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables are presented in Table 1.

Attachment style—a key factor in emotional coping—also plays a critical role in infertility adjustment. Based on attachment theory, early relationships with caregivers shape how individuals interact with others in adulthood [7]. Adults with secure attachment typically possess self-worth, trust in others, and the capacity for intimacy, while those with insecure avoidant or ambivalent attachment styles may struggle with trust, fear of intimacy, and emotional instability [8]. These differences affect how infertile women experience and express distress. Securely attached women are more likely to seek and accept spousal support, enhancing marital satisfaction and emotional stability [9]. On the contrary, insecurely attached women may conceal their infertility due to fear of judgment or dependency, which exacerbates their psychological distress.

There is substantial evidence that attachment styles are associated with self-compassion and mental health. Research suggests that secure attachment fosters self-compassion and psychological resilience [10], whereas insecure attachment is linked to self-criticism, rumination, and reduced emotional well-being [11]. Considering the aforementioned points, attachment styles are confirmed to have a marked impact on self-compassion, which serves as an effective strategy for managing emotions in pregnancy [12]. Securely attached individuals—having received consistent care and validation—tend to internalize warmth and understanding, while those with inconsistent or neglectful caregivers often struggle to extend compassion to themselves. Consequently, self-compassion functions as a crucial mediator between attachment styles and emotional outcomes, such as mental rumination [13]. Based on these findings, it is proposed that attachment style significantly influences both self-compassion and infertility-related mental rumination. Secure attachment may serve as a protective factor, mitigating ruminative thinking through enhanced self-compassion, while insecure attachment increases vulnerability to negative self-reflection and emotional distress. Therefore, fostering self-compassion could be a valuable therapeutic approach to help infertile women manage their emotions, reduce maladaptive rumination, and improve their psychological well-being.

Objectives

Infertility causes significant psychological, social, and financial distress for women, often leading to reduced quality of life and self-blame. The enhancement of self-compassion may alleviate these difficulties, helping women value themselves beyond childbearing and improving treatment outcomes. In light of the aforementioned issues, the present study evaluates the relationships among attachment styles, self-compassion, and mental rumination to support the proposed model. If confirmed, targeted interventions aimed at the mitigation of rumination in infertile women can be developed with greater confidence.

Materials and Methods

Research Design and Participants

This cross-sectional correlational study employed structural equation analysis. The research population consisted of all primary infertile women referring to fertility centers of Yazd, Fars, Kerman, and Isfahan provinces in Iran in 2020. They were clinically diagnosed with infertility. A total of 346 women were selected via the available sampling method. The inclusion criteria entailed passing at least three years of married life, a tendency to have children, primary infertility, a continual treatment period of at least one year after infertility diagnosis, and the age range of 20-40 years. On the other hand, participants with infertility-related physical disorders, psychiatric disorders, and a history of using psychiatric medications were excluded from the study. The candidates’ compliance with the inclusion criteria was assessed by the interviews conducted with them and reviews of their medical history.

Measures

Adult Attachment Inventory (AAI): The Persian version of the adult attachment scale was designed based on Hazan and Shaver’s questionnaire. The validity and reliability of this scale were confirmed among Tehran University students [14]. The AAI includes 15 items that assess the secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent styles of attachment based on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for these three styles were found to be 0.86, 0.84, and 0.85, respectively (0.86, 0.83, and 0.84 for females and 0.84, 0.85, and 0.86 for males). The convergent and discriminant validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability of AAI were confirmed. The test-retest reliability for secure, avoidant, and anxious/ambivalent were reported as 0.82, 0.78, and 0.75, respectively [14].

Self-compassion scale (SCS): This 26-item questionnaire encompasses six subscales of self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification [4]. The items are scored based on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always). The alpha coefficients of the Persian version of SCS were reported as 0.91, 0.77, 0.70, 0.72, 0.72, 0.68, and 0.67 for total items, self-kindness, self-judgement, common humanity, isolation, mindfulness, and over-identification subscales, respectively [15]. The factor structure of the Persian version of SCS in an Iranian sample was confirmed by confirmatory factor analysis [15]. The content validity index and content validity ratio of the Persian version of SCS were obtained as 0.82-0.95 and 0.78-0.95 [16].

Ruminative response scale (RRS): The RRS contains 22 items scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always). The total score ranged from 22 to 88, with higher scores suggesting higher levels of mental rumination [17]. The Cronbach's alpha and test-retest reliability coefficient of RRS were 0.88-0.92 and 0.67 (Luminet, 2003). The Cronbach’s alpha for the Persian version of RRS was 0.88 in a sample of Iranian students. The Persian version of the RRS has a significant positive correlation with anxiety and depression [18]. The factor structure of the Persian version of the RRS was confirmed, and the test-retest reliability was 0.67 [19].

Data Analysis

Structural equation modeling and Pearson correlations were used to assess variable relationships using SPSS and AMOS software packages (version 16). The missing data were replaced with participants’ responses within the same domain. Significance was set at P<0.05. The assumptions for structural equation analysis, including nonlinearity (via variance inflation and tolerance tests), independence of errors (Durbin-Watson test), and linearity (scatter plots), were tested. Indirect effects were analyzed using the bootstrapping technique.

Results

The mean age of participants was 28.56±3.93 years, respectively. All the participants had the experience of one marriage. The immediate relatives of 229 participants (66.2%) had no infertility history; nonetheless, the case was positive for the other 117 (33.8%) participants. Moreover, 30, 103, 114, and 99 subjects had been married for less than 3, 3-6, 7-9, and more than 9 years, respectively. Regarding infertility treatment, 51 cases were making their first attempt to treat infertility, 51 others had a previous failed attempt, 131 had 2-4 failed attempts, and 111 had more than four failed attempts to treat their infertility. The means, standard deviations, and correlations among the variables are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations among the variables

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Mean | SD |

| 1. Secure attachment | 1 | 10.63 | 4.36 | |||

| 2. Avoidant attachment | .13* | 1 | 9.92 | 3.20 | ||

| 3. Anxious/ambivalent attachment | -.07 | -.02 | 1 | 9.18 | 4.21 | |

| 4. Self-compassion | .33** | -.20** | -.32** | 1 | 72.12 | 15.94 |

| 5. Mental rumination | -.28* | .33** | .37** | -.46** | 53.71 | 13.81 |

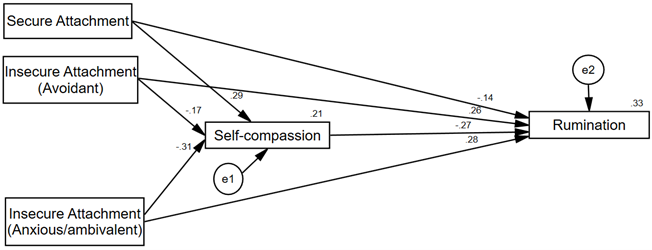

As illustrated in Table 1, attachment style was positively correlated with self-compassion and negatively related to mental rumination. Insecure avoidant and anxious/ambivalent attachments were negatively associated with self-compassion but positively correlated with rumination. Self-compassion and mental rumination were negatively correlated (P<0.01). The proposed model was tested using structural equation modeling, with assumptions of normality, non-linearity, and error independence all being confirmed. Figure 1 presents the model schematically.

As depicted in Figure 1, secure attachment positively predicted self-compassion (β=0.29) and negatively predicted mental rumination (β=–0.14). On the contrary, insecure avoidant and ambivalent attachment styles negatively affected self-compassion and positively affected rumination. Self-compassion also had a significant negative effect on mental rumination (P<0.01). Model fit indices demonstrated good fit: χ² = 8.45 (P<0.01), χ²/df=2.81, GFI=0.99, NFI=0.96, IFI=0.98, CFI=0.98, and RMSEA=0.07, all within desirable thresholds. Bootstrapping confirmed that self-compassion significantly mediated the relationship between attachment styles and rumination. Indirect path coefficients were β=0.08 for secure attachment, β=0.05 for insecure avoidant, and β=0.08 for ambivalent attachment (P<0.01). These results validated the proposed model, demonstrating that attachment styles affect infertile women’s mental rumination both directly and indirectly through self-compassion.

Discussion

Analysis of the results showed that Compassion- As evidenced by the results of this study, attachment styles are related to both self-compassion and mental rumination in infertile women, and self-compassion mediates the relationship between attachment styles and mental rumination. It was also illustrated that the secure style of attachment has a positive and significant relationship with self-compassion. In other words, those who feel secure about their ability to cope with threats and challenges, tend to use effective strategies to tackle problems, and seek support [20] are more compassionate themselves. Individuals who have a sense of security pursue their goals with assurance as they believe they have the support of others in critical conditions [8, 21]. They are also compassionate to themselves [9, 22, 23] owing to their optimistic view of life and non-dismal assessment of threats and dangers [20].

Consistent with previous studies, in this research, avoidant and anxious/ambivalent attachment styles were found to have a negative and significant correlation with self-compassion [10, 22, 23]. Unlike secure individuals, those with a mildly or severely avoidant attachment style, as well as a mildly or severely anxious attachment style, report a lower level of self-compassion [24-26] as they find it challenging to engage in acts of kindness or forgiveness. Avoidant and anxious attachment styles involve different mechanisms for the adjustment of feelings and emotions; nonetheless, both make individuals highly susceptible to stress. Individuals with insecure attachment take a defensive position when facing a crisis, suppress their emotions, and deny their need for compassion in stressful conditions [23]. Consequently, they are rarely kind to themselves as they find it hard to practice self-compassion [10].

In this study, the ambivalent style of attachment emerged to have a stronger negative correlation with self-compassion compared to the avoidant attachment style. In other words, the infertile women who were anxious or ambivalent in their relations were less compassionate to themselves. According to Hazan and Shaver [8], avoidant attachment involves a negative view of others and a positive view of oneself. It was also argued that some people at a high level of avoidant attachment may seem to hold positive attitudes toward themselves, and therefore feel entitled to greater compassion [24]. Nevertheless, they reproach themselves and exhibit low self-compassion due to high self-expectation, excessive need for self-dependence, and lack of tendency to disclose one’s problems to others [27]. Of the three major styles, anxious/ambivalent attachment involves negative attitudes toward both oneself and others [7]. There has always been substantial evidence that anxious/ambivalent attachment is negatively correlated with self-compassion and positively associated with self-criticism. Individuals with stronger anxious/ambivalent attachment are less inclined to show kindness towards themselves and tend to be more critical of their flaws [11].

This study provided evidence for the low rate of mental rumination in securely attached infertile women, in contrast to the profuse practice of this phenomenon in those with insecure anxious/avoidant attachment. It seems that a secure attachment gives more support, provides better coping strategies for problem solving, and maintains psychological well-being throughout stressful events [20]. It also ensures the skill of emotional self-regulation [28]. During a crisis, secure people are able to adjust their emotions and assess the factors responsible for that situation [20]. In the case of infertile women, a sense of security in attachments helps them adjust their emotions when a problem comes up, choose proper problem-solving strategies, seek support from others [22], and therefore avoid mental rumination [28].

It was also revealed that avoidant and anxious attachment styles have a positive and significant correlation with mental rumination. Hazan and Shaver [8] indicated that, after a difficult experience, insecure anxious individuals use hyperactive strategies, such as mental rumination. This is while those with an avoidant style resort to non-activating emotional adjustment techniques, such as suppression, cognitive distancing, and emotional isolation [20]. Accordingly, it is natural for infertile women with avoidant and anxious attachment styles to suppress their emotions, conceal those emotions by keeping away from others, and face problems with maladaptive strategies, such as mental rumination. Nevertheless, anxious/ambivalent infertile women have exaggerated concerns about their inability to bear children and the absence of a safe, affective haven, such as a child. These women may suffer from adverse consequences, such as mental rumination [22, 28]. In general, the strategies that insecure people adopt to cope with problems stem from fear, anxiety, anger, grief, shame, sin, and despair. The extensive use of these strategies suggests their vulnerability in the face of emotional threats [20]. It can be argued that a woman with an insecure attachment style begins to feel more insecure when she finds out about her infertility [22].

In agreement with previous studies, the current research highlighted a negative and significant relationship between self-compassion and mental rumination [29-31]. Self-compassion enhances emotional resilience, and those who are endowed with this practice are less prone to depression and mental rumination [31]. It has also been reported that self-compassion discourages self-criticism, anxiety, suppression of thoughts, and neurotic perfectionism; however, it enhances life satisfaction and public relationships [4]. Frostadottir and Dorjee [32] studied a group of patients suffering from depression, anxiety, and stress by comparing the effects of cognitive therapy based on mindfulness and self-compassion enhancement on mental rumination. According to them, both treatments could mitigate the symptoms, raise mindfulness, and reduce mental rumination. Therefore, it is recommended to adopt compassion-based therapeutic processes for infertile women to foster self-compassion and reduce their mental rumination. In general, people who have compassionate attitudes toward themselves report low levels of mental rumination and self-criticism [29, 31].

Regarding the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between attachment styles and mental rumination, Neff and McGehee [26] stated that a compassionate style of child-rearing, along with secure attachments, might contribute to self-protection and, consequently, self-compassion. A secure attachment can be claimed to exist only when anxiety and avoidance are at their lowest [25]. People in highly anxious relationships feel incapable and worryingly deal with issues, such as availability and accountability to those whom they deem important. Individuals in avoidant relationships often struggle with intimacy, suppress emotional responses, and depend excessively on themselves in distressing situations. It has been found that the lack of supportive child-rearing practices and anxious attachment marked with distrust may result in extreme self-criticism [25]. Moreover, a sense of insecurity in social attachments aggregates infertility-induced problems and imposes concerns about sexual and social relationships [33]. In these circumstances, self-compassion, which could serve as a beneficial factor in mitigating mental rumination during infertility, fails to develop [25].

Conclusion

This study pointed out that secure attachment protects against mental rumination in infertile women, while insecure attachment increases vulnerability to depression and distress. Self-compassion mediates this relationship, helping women reduce self-blame and cope more effectively. By fostering emotional adjustment, self-compassion can improve the quality of life, enhance treatment adherence, and reduce infertility-related stress. Compassion-focused interventions are especially beneficial for women with insecure attachment styles, promoting better emotional regulation, interpersonal relationships, and resilience in patriarchal context.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study has some limitations, including non-random sampling and an overrepresentation of educated participants. It also excluded key variables, such as socio-economic status and social or spousal support, due to financial and time constraints. Future research should compare attachment styles, self-compassion, and mental rumination across different socio-economic groups and include moderator variables, such as spousal and societal support, in the proposed model.

Ethical Considerations

Before the commencement of the study, its objectives were explained to participants, and the secrecy of their information was ensured. They all filled out and signed the consent form to participate in the research. The Medical Ethics Committee of Yazd University also approved the research ethically (ID: IR.YAZD.REC.1399.016).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the women who participated in the study.

Authors' Contributions

MS participated in data collection, data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. YR-M participated in study design, drafting, and preparing the manuscript. AC participated in the 96revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/Support

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare. In addition, with the final approval of this article, the authors accept the responsibility for the accuracy and correctness of its contents.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in their entirety in this published article itself.

References

Discussion

Analysis of the results showed that Compassion- As evidenced by the results of this study, attachment styles are related to both self-compassion and mental rumination in infertile women, and self-compassion mediates the relationship between attachment styles and mental rumination. It was also illustrated that the secure style of attachment has a positive and significant relationship with self-compassion. In other words, those who feel secure about their ability to cope with threats and challenges, tend to use effective strategies to tackle problems, and seek support [20] are more compassionate themselves. Individuals who have a sense of security pursue their goals with assurance as they believe they have the support of others in critical conditions [8, 21]. They are also compassionate to themselves [9, 22, 23] owing to their optimistic view of life and non-dismal assessment of threats and dangers [20].

Consistent with previous studies, in this research, avoidant and anxious/ambivalent attachment styles were found to have a negative and significant correlation with self-compassion [10, 22, 23]. Unlike secure individuals, those with a mildly or severely avoidant attachment style, as well as a mildly or severely anxious attachment style, report a lower level of self-compassion [24-26] as they find it challenging to engage in acts of kindness or forgiveness. Avoidant and anxious attachment styles involve different mechanisms for the adjustment of feelings and emotions; nonetheless, both make individuals highly susceptible to stress. Individuals with insecure attachment take a defensive position when facing a crisis, suppress their emotions, and deny their need for compassion in stressful conditions [23]. Consequently, they are rarely kind to themselves as they find it hard to practice self-compassion [10].

In this study, the ambivalent style of attachment emerged to have a stronger negative correlation with self-compassion compared to the avoidant attachment style. In other words, the infertile women who were anxious or ambivalent in their relations were less compassionate to themselves. According to Hazan and Shaver [8], avoidant attachment involves a negative view of others and a positive view of oneself. It was also argued that some people at a high level of avoidant attachment may seem to hold positive attitudes toward themselves, and therefore feel entitled to greater compassion [24]. Nevertheless, they reproach themselves and exhibit low self-compassion due to high self-expectation, excessive need for self-dependence, and lack of tendency to disclose one’s problems to others [27]. Of the three major styles, anxious/ambivalent attachment involves negative attitudes toward both oneself and others [7]. There has always been substantial evidence that anxious/ambivalent attachment is negatively correlated with self-compassion and positively associated with self-criticism. Individuals with stronger anxious/ambivalent attachment are less inclined to show kindness towards themselves and tend to be more critical of their flaws [11].

This study provided evidence for the low rate of mental rumination in securely attached infertile women, in contrast to the profuse practice of this phenomenon in those with insecure anxious/avoidant attachment. It seems that a secure attachment gives more support, provides better coping strategies for problem solving, and maintains psychological well-being throughout stressful events [20]. It also ensures the skill of emotional self-regulation [28]. During a crisis, secure people are able to adjust their emotions and assess the factors responsible for that situation [20]. In the case of infertile women, a sense of security in attachments helps them adjust their emotions when a problem comes up, choose proper problem-solving strategies, seek support from others [22], and therefore avoid mental rumination [28].

It was also revealed that avoidant and anxious attachment styles have a positive and significant correlation with mental rumination. Hazan and Shaver [8] indicated that, after a difficult experience, insecure anxious individuals use hyperactive strategies, such as mental rumination. This is while those with an avoidant style resort to non-activating emotional adjustment techniques, such as suppression, cognitive distancing, and emotional isolation [20]. Accordingly, it is natural for infertile women with avoidant and anxious attachment styles to suppress their emotions, conceal those emotions by keeping away from others, and face problems with maladaptive strategies, such as mental rumination. Nevertheless, anxious/ambivalent infertile women have exaggerated concerns about their inability to bear children and the absence of a safe, affective haven, such as a child. These women may suffer from adverse consequences, such as mental rumination [22, 28]. In general, the strategies that insecure people adopt to cope with problems stem from fear, anxiety, anger, grief, shame, sin, and despair. The extensive use of these strategies suggests their vulnerability in the face of emotional threats [20]. It can be argued that a woman with an insecure attachment style begins to feel more insecure when she finds out about her infertility [22].

In agreement with previous studies, the current research highlighted a negative and significant relationship between self-compassion and mental rumination [29-31]. Self-compassion enhances emotional resilience, and those who are endowed with this practice are less prone to depression and mental rumination [31]. It has also been reported that self-compassion discourages self-criticism, anxiety, suppression of thoughts, and neurotic perfectionism; however, it enhances life satisfaction and public relationships [4]. Frostadottir and Dorjee [32] studied a group of patients suffering from depression, anxiety, and stress by comparing the effects of cognitive therapy based on mindfulness and self-compassion enhancement on mental rumination. According to them, both treatments could mitigate the symptoms, raise mindfulness, and reduce mental rumination. Therefore, it is recommended to adopt compassion-based therapeutic processes for infertile women to foster self-compassion and reduce their mental rumination. In general, people who have compassionate attitudes toward themselves report low levels of mental rumination and self-criticism [29, 31].

Regarding the mediating role of self-compassion in the relationship between attachment styles and mental rumination, Neff and McGehee [26] stated that a compassionate style of child-rearing, along with secure attachments, might contribute to self-protection and, consequently, self-compassion. A secure attachment can be claimed to exist only when anxiety and avoidance are at their lowest [25]. People in highly anxious relationships feel incapable and worryingly deal with issues, such as availability and accountability to those whom they deem important. Individuals in avoidant relationships often struggle with intimacy, suppress emotional responses, and depend excessively on themselves in distressing situations. It has been found that the lack of supportive child-rearing practices and anxious attachment marked with distrust may result in extreme self-criticism [25]. Moreover, a sense of insecurity in social attachments aggregates infertility-induced problems and imposes concerns about sexual and social relationships [33]. In these circumstances, self-compassion, which could serve as a beneficial factor in mitigating mental rumination during infertility, fails to develop [25].

Conclusion

This study pointed out that secure attachment protects against mental rumination in infertile women, while insecure attachment increases vulnerability to depression and distress. Self-compassion mediates this relationship, helping women reduce self-blame and cope more effectively. By fostering emotional adjustment, self-compassion can improve the quality of life, enhance treatment adherence, and reduce infertility-related stress. Compassion-focused interventions are especially beneficial for women with insecure attachment styles, promoting better emotional regulation, interpersonal relationships, and resilience in patriarchal context.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

This study has some limitations, including non-random sampling and an overrepresentation of educated participants. It also excluded key variables, such as socio-economic status and social or spousal support, due to financial and time constraints. Future research should compare attachment styles, self-compassion, and mental rumination across different socio-economic groups and include moderator variables, such as spousal and societal support, in the proposed model.

Ethical Considerations

Before the commencement of the study, its objectives were explained to participants, and the secrecy of their information was ensured. They all filled out and signed the consent form to participate in the research. The Medical Ethics Committee of Yazd University also approved the research ethically (ID: IR.YAZD.REC.1399.016).

Acknowledgments

We thank all the women who participated in the study.

Authors' Contributions

MS participated in data collection, data analysis, and prepared the manuscript. YR-M participated in study design, drafting, and preparing the manuscript. AC participated in the 96revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/Support

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest to declare. In addition, with the final approval of this article, the authors accept the responsibility for the accuracy and correctness of its contents.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in their entirety in this published article itself.

References

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100(4):569–82. [DOI:10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569] [PMID]

- Arnow BA, Spangler D, Klein DN, Burns DD. Rumination and distraction among chronic depressives in treatment: A structural equation analysis. Cogn Ther Res. 2004;28(1):67–83. [DOI: 10.1023/B:COTR.0000016931.37807.ab]

- Taguibao JA, Bance LO. The point of waiting: A phenomenological study on infertility coping experiences among Filipino women with reproductive concerns. J Crit Rev. 2020;7(19):2994–3010. [DOI:10.31838/jcr.07.19.364]

- Neff KD. The self-compassion scale is a valid and theoretically coherent measure of self-compassion. Mindfulness (N Y). 2016;7(1):264–74. [DOI:10.1007/s12671-015-0479-3]

- Sadiq U, Rana F, Munir M. Marital quality, self-compassion and psychological distress in women with primary infertility. Sex Disabil. 2022;40(1):167–77. [DOI:10.1007/s11195-021-09708-w]

- Raque-Bogdan TL, Hoffman MA. The relationship among infertility, self-compassion, and well-being for women with primary or secondary infertility. Psychol Women Q. 2015;39(4):484–96. [DOI:10.1177/0361684315576208]

- Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987;52(3):511–24. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.52.3.511] [PMID]

- Hazan C, Shaver PR. Deeper into attachment theory. Psychol Inq. 1994;5(1):68–79. [DOI:10.1207/s15327965pli0501_15]

- Saleem S, Qureshi NS, Mahmood Z. Attachment, perceived social support and mental health problems in women with primary infertility. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2019;8(6):2533–41. [DOI:10.18203/2320-1770.ijrcog20192463]

- Wei M, Liao KYH, Ku TY, Shaffer PA. Attachment, self-compassion, empathy, and subjective well-being among college students and community adults. J Pers. 2011;79(1):191–221. [DOI:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00677.x]

- Heflin S. Attachment and shame-coping style: A relationship mediated by fear of compassion? Unpublished Dissertation. Kansas City (MO): Univ Missouri-Kansas City; 2015. [Link]

- Ogueji IA. Experiences and predictors of psychological distress in pregnant women living with HIV. Br J Health Psychol. 2021;26(3):882–901. [DOI:10.1111/bjhp.12510] [PMID]

- Besharat MA, Teimourpour N, Rahiminezhad A, Hossein Rashidi B, Gholamali Lavasani M. The mediating role of cognitive emotion regulation strategies on the relationship between attachment styles and ego strength with adjustment to infertility in women. Contemp Psychol. 2016;11(1):3–20. [Link]

- Besharat MA. Development and validation of Adult Attachment Inventory. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2011;30:475–9. [DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.093]

- Shahbazi M, Rajabi G, Maghami E, Jolodari A. Confirmatory factor analysis of the Persian version of the Self-Compassion Rating Scale-Revised. Psychol Methods Models. 2015;6(19):31–46. [Link]

- Hasani J, Pasdar K. The assessment of confirmatory factor structure, validity, and reliability of Persian version of Self-Compassion Scale (SCS-P) in Ferdowsi University of Mashhad in 2013. J Rafsanjan Univ Med Sci. 2017;16(8):727–42. [Link]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J. A prospective study of depression and posttraumatic stress symptoms after a natural disaster: the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(1):115–21. [DOI:10.1037//0022-3514.61.1.115] [PMID]

- Bagherinezhad M, Fadardi JS, Tabatabayi SM. The relationship between rumination and depression in a sample of Iranian students. Res Clin Couns Psychol. 2010;11(1):21–38. [Link]

- Tanhaye RF, Torkamani M, Mirshahi S, Hajibakloo N, Kareshki H. Validity and reliability assessment of the Persian version of the Co-Rumination Questionnaire. J Clin Psychol. 2021;13(1):79–87. [DOI:10.22075/jcp.2021.20312.1874]

- Mikulincer M, Shaver PR. Attachment orientations and emotion regulation. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;25:6–10. [DOI:10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.006] [PMID]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attach Hum Dev. 2002;4(2):133–61. [DOI:10.1080/14616730210154171] [PMID]

- Besharat MA, Naghshineh N, Ganji P, Tavalaeyan F. The moderating role of attachment styles on the relationship of alexithymia and fear of intimacy with marital satisfaction. Int J Psychol Stud. 2014;6(3):106–17. [DOI:10.5539/ijps.v6n3p106]

- Pepping CA, Davis PJ, O'Donovan A, Pal J. Individual differences in self-compassion: The role of attachment and experiences of parenting in childhood. Self Identity. 2015;14(1):104–17. [DOI:10.1080/15298868.2014.955050]

- Raque-Bogdan TL, Ericson SK, Jackson J, Martin HM, Bryan NA. Attachment and mental and physical health: self-compassion and mattering as mediators. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(2):272–8. [DOI:10.1037/a0023041]

- Raque-Bogdan TL, Piontkowski S, Hui K, Ziemer KS, Garriott PO. Self-compassion as a mediator between attachment anxiety and body appreciation: An exploratory model. Body Image. 2016;19:28–36. [DOI:10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.001] [PMID]

- Neff KD, McGehee P. Self-compassion and psychological resilience among adolescents and young adults. Self Identity. 2010;9(3):225–40. [DOI:10.1080/15298860902979307]

- Donarelli Z, Lo Coco G, Gullo S, Marino A, Volpes A, Allegra A. Are attachment dimensions associated with infertility-related stress in couples undergoing their first IVF treatment? A study on the individual and cross-partner effect. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(11):3215–25. [DOI:10.1093/humrep/des307] [PMID]

- Collins JA. Narratives and attachment styles: Role of rumination, reflection and self-compassion in relation to psychological health and well-being. Unpublished Dissertation. Hawthorn (VIC): Swinburne Univ Technol; 2021. [Link]

- Brown SL, Hughes M, Campbell S, Cherry MG. Could worry and rumination mediate relationships between self-compassion and psychological distress in breast cancer survivors? Clin Psychol Psychother. 2020;27(1):1–10. [DOI:10.1002/cpp.2399]

- Gilbert P. Compassion: Concepts, Research and Applications. New York: Routledge; 2017. [Link]

- Hodgetts J, McLaren S, Bice B, Trezise A. The relationships between self-compassion, rumination, and depressive symptoms among older adults: the moderating role of gender. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25(12):2337–46. [DOI:10.1080/13607863.2020.1824207] [PMID]

- Frostadottir AD, Dorjee D. Effects of mindfulness based cognitive therapy (MBCT) and compassion focused therapy (CFT) on symptom change, mindfulness, self-compassion, and rumination in clients with depression, anxiety, and stress. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1099. [DOI:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01099] [PMID]

- Elyasi F, Parkoohi PI, Naseri M, Gelekolaee KS, Hamedi M, Peyvandi S, et al. Relationship between coping/attachment styles and infertility-specific distress in Iranian infertile individuals: A cross-sectional study. Int J Reprod Biomed. 2021;19(4):347–60. [DOI:10.18502/ijrm.v19i4.9061] [PMID]

Article Type: Research Article |

Subject:

Health Education and Promotion

Received: 2025/09/5 | Accepted: 2025/09/20 | Published: 2025/09/25

Received: 2025/09/5 | Accepted: 2025/09/20 | Published: 2025/09/25

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |