Volume 12, Issue 3 (September 2025)

Avicenna J Neuro Psycho Physiology 2025, 12(3): 124-132 |

Back to browse issues page

Ethics code: (IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.438)

Download citation:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

BibTeX | RIS | EndNote | Medlars | ProCite | Reference Manager | RefWorks

Send citation to:

Shahrezaei A, Sohani M, Rahimi B, Nasirinezhad F. Impact of Intrapreneurial Amniotic Mesenchymal Stem Cells (MSC)-conditioned Medium on Spinal Calcitonin Gene-related peptide (CGRP) in Peripheral Neuropathy Models. Avicenna J Neuro Psycho Physiology 2025; 12 (3) :124-132

URL: http://ajnpp.umsha.ac.ir/article-1-526-en.html

URL: http://ajnpp.umsha.ac.ir/article-1-526-en.html

1- School of Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2- Lois Pope Life Center, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

3- Department of Physiology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran & Physiology Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,nasirinezhad.f@iums.ac.ir

2- Lois Pope Life Center, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA

3- Department of Physiology, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran & Physiology Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran ,

Keywords: Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) levels, Chronic constriction injury (CCI), Conditioned medium (CM), Human amniotic stem cells, Neuropathic pain

Full-Text [PDF 665 kb]

(66 Downloads)

| Abstract (HTML) (867 Views)

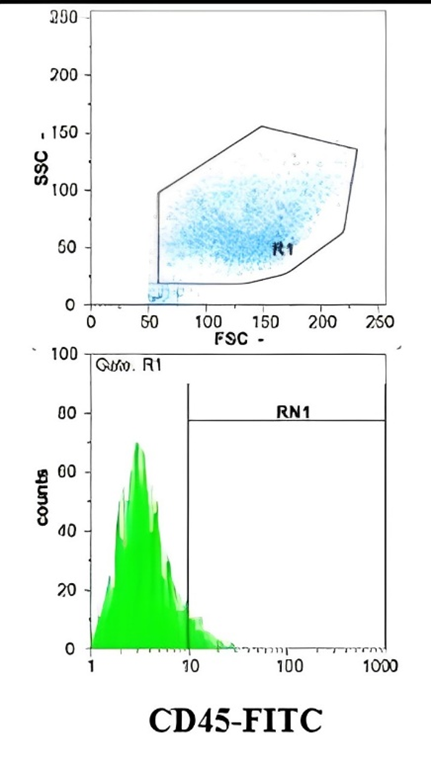

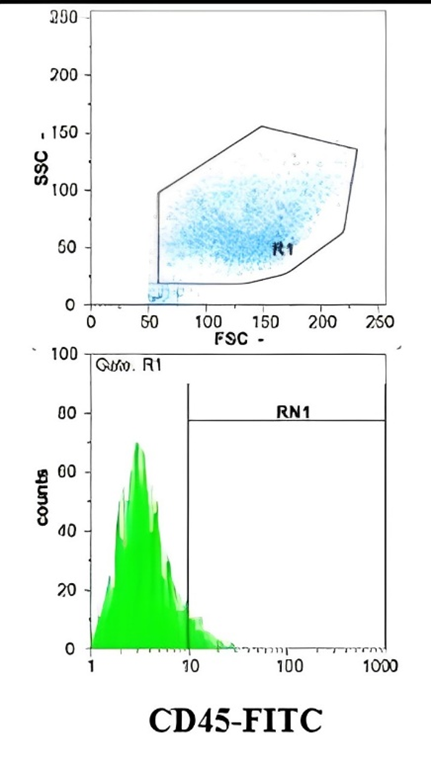

Figure 1. Evaluation of Surface Marker Expression in Amniotic-derived Stem Cells by Flow Cytometry

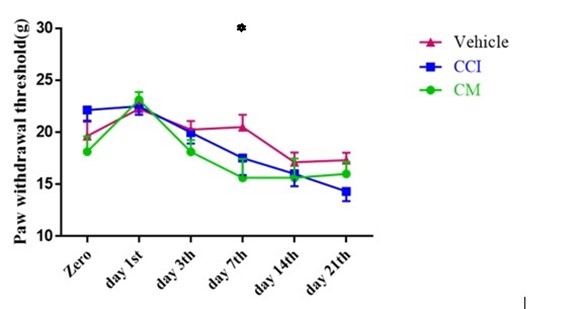

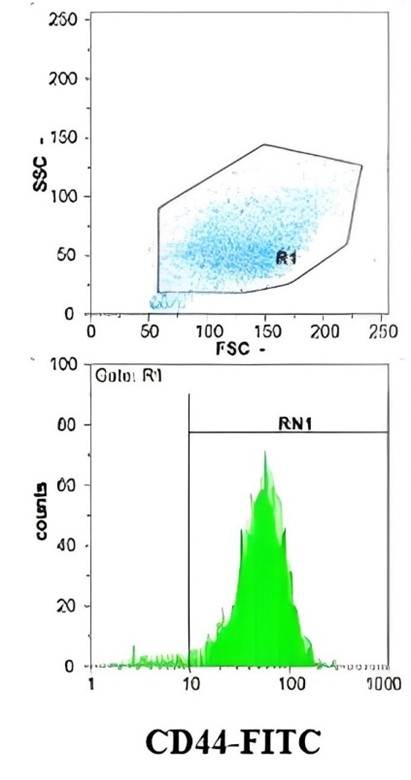

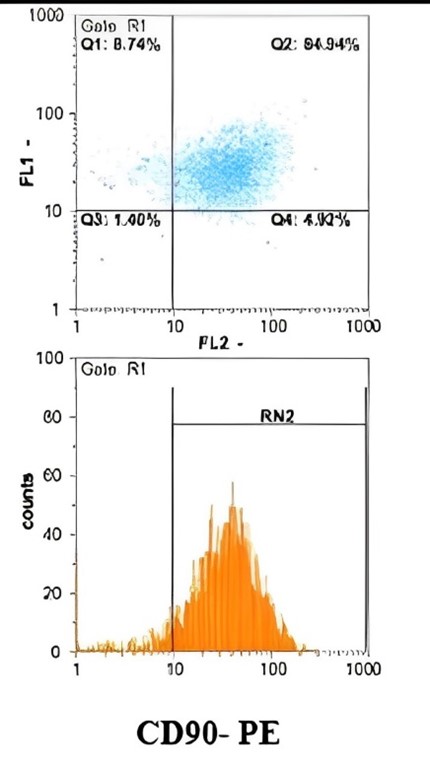

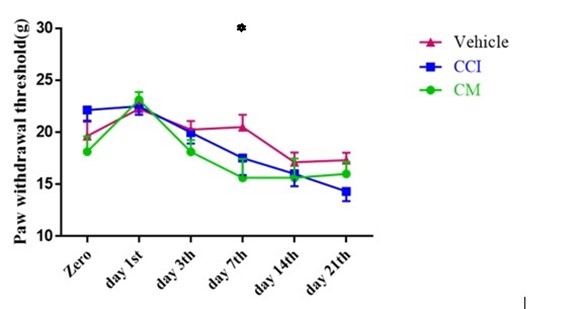

Figure 2. The Effect of Intrathecal Injection of Conditioned Media on Mechanical Sensitivity Threshold After Induction of Neuropathic Pain, Based on the Randall Behavioral Test. In all groups, the mechanical sensitivity threshold decreased after CCI induction. In rats receiving conditioned media, the reduction in sensitivity is significant compared to the CCI and Vehicle groups from the seventh day. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Each group consisted of eight rats. * denotes a statistically significant difference relative to the Vehicle group (P < 0.01).

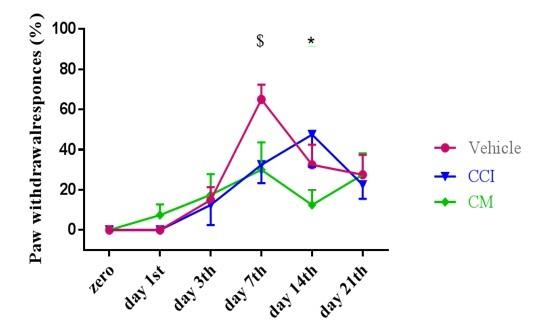

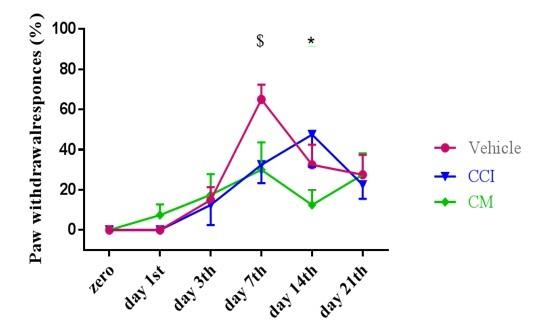

Figure 3. The Effect of Intrathecal Injection of Conditioned Media After the Induction of Neuropathic Pain on the Cold Stimulation Threshold Based on the Acetone Behavioral Test. In all groups, the cold stimulation threshold decreased after CCI induction. In rats receiving conditioned media, the reduction in stimulation threshold was significantly less compared to the CCI and Vehicle groups from day seven onwards. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Each experimental group included eight rats. An asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant difference compared to the nerve injury group (P < 0.05). The symbol ($) indicates a substantial difference from the vehicle group (P < 0.05).

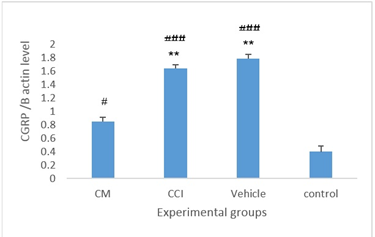

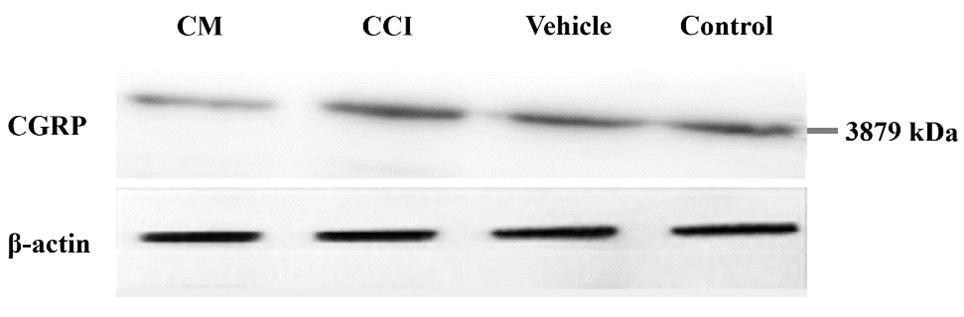

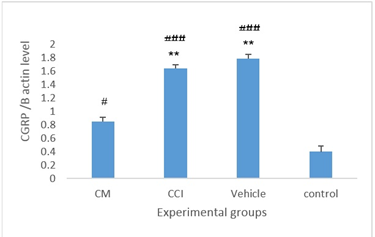

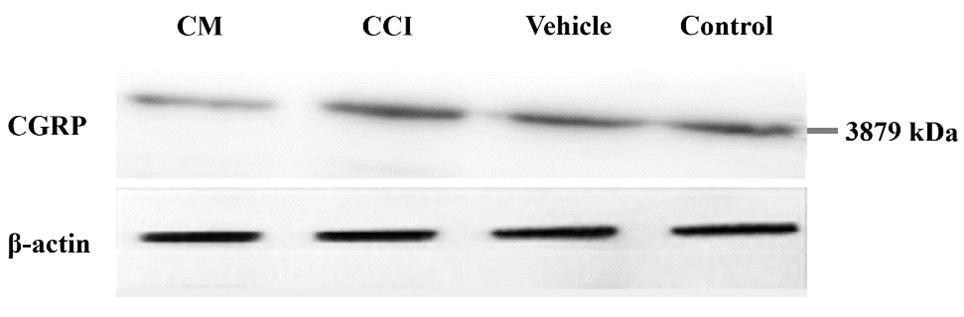

Figure 1. The Expression Levels Of Spinal Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (Cgrp)/Β-Actin Protein Within The Spinal Cords Of Animals Across The Experimental Groups. Data are reported as mean ± Sem. ** Statistically significant difference in comparison to the cm group (p < 0.01)

### Significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively).

Full-Text: (48 Views)

Background

Neuropathic pain, accounting for approximately 20%–25% of chronic pain cases, remains a major clinical challenge due to its limited responsiveness to pharmacological treatments, which are effective in only 40%–60% of patients [1]. Arising from lesions or diseases affecting the somatosensory nervous system, neuropathic pain is driven by multifactorial mechanisms, including peripheral sensitization, ectopic neuronal discharges, disinhibition of pain pathways, and central sensitization within the spinal cord and brain [2]. Neuroinflammatory processes, mediated by activated glial cells and immune mediators, further exacerbate nociceptive signaling, contributing to hyperalgesia, allodynia, and persistent pain states that remain largely resistant to conventional pharmacological interventions [2]. This highlights the urgent need for innovative therapeutic approaches that address these underlying mechanisms.

Stem cells have emerged as a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, offering the potential to repair or regenerate damaged tissues resulting from injuries or degenerative conditions [3]. Beyond their therapeutic applications, stem cell-based interventions have advanced our understanding of cellular behavior, tissue remodeling, and regenerative processes, paving the way for novel treatment strategies in various pathological contexts, including neuropathic pain [3].

Among the various sources, stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and embryonic tissues have been investigated for their potential in repairing peripheral nerve injuries [4]. Proposed mechanisms include trophic support, modulation of the immune response, remyelination, and extracellular matrix remodeling [4]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are characterized by the presence or absence of specific surface markers [5]. Among these, CD44, an adhesion molecule, is highly expressed in MSCs and plays a pivotal role in cell-matrix interactions, migration, and tissue repair (REF) [6]. Conversely, CD45, a pan-leukocyte marker, is absent in MSCs, confirming their non-hematopoietic origin (REF) [7]. Additionally, CD90 (Thy-1), a glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein, is considered a hallmark of stemness, supporting self-renewal and differentiation capacity (REF) [6]. Including these markers in phenotypic characterization is essential to ensure the purity and functional potential of MSC-derived products used in regenerative therapies, such as conditioned medium (CM) [8].

Nevertheless, contemporary scholarly attention has transitioned towards the therapeutic prospects of CM, specifically the secretome derived from cultured stem cells, which encompasses a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including cytokines, growth factors, metabolites, and matrix proteins [9]. These secretions may facilitate tissue repair and modulate inflammation and pain pathways in various neurological conditions, potentially counteracting the neuroinflammatory and sensitizing aspects of neuropathic pain pathophysiology [10].

One key molecule implicated in pain transmission is calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a neuropeptide released by primary sensory neurons during persistent pain states, such as migraine and neuropathy [11]. In the context of neuropathic pain, CGRP exacerbates pathophysiology by promoting neurogenic inflammation through vasodilation and immune cell activation and contributing to central sensitization via enhanced synaptic transmission in the spinal dorsal horn [12]. Elevated CGRP levels following nerve injury amplify nociceptive hypersensitivity, making it a critical mediator in the transition from acute to chronic pain [13]. Modulating CGRP signaling may represent a practical approach for attenuating neuropathic pain by interrupting maladaptive processes.

Despite growing evidence for stem cell-derived CMs' regenerative and immunomodulatory properties, their effects on pain and spinal CGRP expression in peripheral nerve injury models have been inadequately studied [14]. CGRP is pivotal in promoting nociceptive signal transmission in the spinal cord.

Objectives

Therefore, this study aimed to elucidate the effects of intrapreneurial administration of CM derived from human amniotic MSC on pain-related behaviors and spinal CGRP in a rat model characterized by chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve [15].

Materials and Methods

Forty adult male Wistar rats (200–250 g) were obtained from the Experimental and Comparative Studies Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences [16]. Three rats, one from the CCI group and two from the vehicle group, died during the course of the experiment and were replaced to maintain group consistency. All animals were housed under standardized laboratory conditions, including a 12:12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00), a controlled ambient temperature of 21°C ± 1°C, relative humidity maintained at approximately 45%, and unrestricted access to food and water [16]. All procedures complied with National Institutes of Health and national animal research guidelines (Ethics Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.1445).

Experimental Groups and Randomization

The animals were randomly allocated to four groups (n=10): control (no intervention), CCI (nerve injury), CCI + intraneural injection of CM, and CCI + intraneural injection of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (vehicle).

Induction of Chronic Constriction Injury (CCI)

CCI was induced by exposing the left sciatic nerve via a 2-cm incision parallel to the iliac crest under anesthesia (ketamine 80 mg/kg, xylazine 8 mg/kg, i.p.) [18]. The nerve was separated and loosely ligated at four points (1 mm apart) using 4-0 chromic gut sutures without compromising blood flow. The muscle and skin were sutured, the site was disinfected, and covered with tetracycline ointment [19].

Preparation of Conditioned Medium (CM)

CM was derived from fourth-passage human amniotic MSCs. MSCs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and other standard growth factors under normoxic conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). After reaching 80%–90% confluence, the culture medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM, and the cells were incubated for an additional 7 days to allow secretion of bioactive factors. The supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 1600 rpm for 5 minutes to remove cellular debris, and passed through a 0.22-μm sterile filter to obtain the final CM [20].

Administration of Conditioned Medium (CM) or Vehicle

Thirty minutes post-CCI induction, 10 µL of CM was slowly injected into the sciatic nerve sheath proximal to the ligation site (near the fourth ligation point) over 2 minutes using a Hamilton syringe [17, 21]. The Vehicle group received an equivalent volume (10 µL) of plain DMEM administered similarly.

Behavioral Assessments of Pain

Pain-related behaviors were evaluated using the plantar test (for thermal hyperalgesia), acetone test (for cold allodynia), and Randall–Selitto test (for mechanical hyperalgesia) [16, 22]:

Plantar Test: Thermal hyperalgesia was assessed by measuring the latency to hind paw withdrawal from an infrared heat source. A cutoff time of 25 seconds was implemented to avoid tissue damage. Each rat was tested in three trials separated by 10-minute intervals, and the average latency was recorded [23].

Randall–Selitto Test: Mechanical hyperalgesia was quantified by applying incrementally increasing pressure to the hind paw until a withdrawal response was elicited. At least two trials per rat were conducted at 1-minute intervals, and the mean pressure threshold was calculated [24].

Acetone Test: Cold allodynia was evaluated by applying a single drop of acetone to the plantar surface of the hind paw. Behavioral responses (e.g., withdrawal, licking, or shaking) were scored over five trials, with 1-minute intervals between applications [25].

Assessment of Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Expression by Western Blotting

CGRP expression in the lumbar spinal cord was analyzed using western blotting [26]. Rats were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneally [27]. Following laminectomy, the lumbar spinal cord (L4–L6 segments) was excised, rinsed in ice-cold 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen within 3 minutes to minimize protein degradation [28]. Samples were stored at –80°C until processing [29].

Tissues were homogenized in the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors [30]. Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Equal amounts of protein (30–50 µg) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes [31]. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween® 20 detergent (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against CGRP (1:1000 dilution) and β-actin (1:5000, loading control) [32]. After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000) for 1 hour [33]. Bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents and quantified by densitometry with ImageJ software. CGRP expression levels were normalized to β-actin [34].

Results

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis confirmed the mesenchymal nature of the cultured cells. Most (> 95%) cells expressed CD44, supporting their adhesive and migratory properties crucial for regenerative activity. CD45 was undetectable, indicating the absence of hematopoietic cells, while a subset of cells exhibited CD90 expression, consistent with stemness-related characteristics (Figure 1). These findings validated the cellular source of CM utilized in subsequent experiments.

Stem cells have emerged as a cornerstone of regenerative medicine, offering the potential to repair or regenerate damaged tissues resulting from injuries or degenerative conditions [3]. Beyond their therapeutic applications, stem cell-based interventions have advanced our understanding of cellular behavior, tissue remodeling, and regenerative processes, paving the way for novel treatment strategies in various pathological contexts, including neuropathic pain [3].

Among the various sources, stem cells derived from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and embryonic tissues have been investigated for their potential in repairing peripheral nerve injuries [4]. Proposed mechanisms include trophic support, modulation of the immune response, remyelination, and extracellular matrix remodeling [4]. Mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are characterized by the presence or absence of specific surface markers [5]. Among these, CD44, an adhesion molecule, is highly expressed in MSCs and plays a pivotal role in cell-matrix interactions, migration, and tissue repair (REF) [6]. Conversely, CD45, a pan-leukocyte marker, is absent in MSCs, confirming their non-hematopoietic origin (REF) [7]. Additionally, CD90 (Thy-1), a glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored glycoprotein, is considered a hallmark of stemness, supporting self-renewal and differentiation capacity (REF) [6]. Including these markers in phenotypic characterization is essential to ensure the purity and functional potential of MSC-derived products used in regenerative therapies, such as conditioned medium (CM) [8].

Nevertheless, contemporary scholarly attention has transitioned towards the therapeutic prospects of CM, specifically the secretome derived from cultured stem cells, which encompasses a diverse array of bioactive molecules, including cytokines, growth factors, metabolites, and matrix proteins [9]. These secretions may facilitate tissue repair and modulate inflammation and pain pathways in various neurological conditions, potentially counteracting the neuroinflammatory and sensitizing aspects of neuropathic pain pathophysiology [10].

One key molecule implicated in pain transmission is calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP), a neuropeptide released by primary sensory neurons during persistent pain states, such as migraine and neuropathy [11]. In the context of neuropathic pain, CGRP exacerbates pathophysiology by promoting neurogenic inflammation through vasodilation and immune cell activation and contributing to central sensitization via enhanced synaptic transmission in the spinal dorsal horn [12]. Elevated CGRP levels following nerve injury amplify nociceptive hypersensitivity, making it a critical mediator in the transition from acute to chronic pain [13]. Modulating CGRP signaling may represent a practical approach for attenuating neuropathic pain by interrupting maladaptive processes.

Despite growing evidence for stem cell-derived CMs' regenerative and immunomodulatory properties, their effects on pain and spinal CGRP expression in peripheral nerve injury models have been inadequately studied [14]. CGRP is pivotal in promoting nociceptive signal transmission in the spinal cord.

Objectives

Therefore, this study aimed to elucidate the effects of intrapreneurial administration of CM derived from human amniotic MSC on pain-related behaviors and spinal CGRP in a rat model characterized by chronic constriction injury (CCI) of the sciatic nerve [15].

Materials and Methods

Forty adult male Wistar rats (200–250 g) were obtained from the Experimental and Comparative Studies Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences [16]. Three rats, one from the CCI group and two from the vehicle group, died during the course of the experiment and were replaced to maintain group consistency. All animals were housed under standardized laboratory conditions, including a 12:12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on at 06:00), a controlled ambient temperature of 21°C ± 1°C, relative humidity maintained at approximately 45%, and unrestricted access to food and water [16]. All procedures complied with National Institutes of Health and national animal research guidelines (Ethics Code: IR.IUMS.REC.1399.1445).

Experimental Groups and Randomization

The animals were randomly allocated to four groups (n=10): control (no intervention), CCI (nerve injury), CCI + intraneural injection of CM, and CCI + intraneural injection of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (vehicle).

Induction of Chronic Constriction Injury (CCI)

CCI was induced by exposing the left sciatic nerve via a 2-cm incision parallel to the iliac crest under anesthesia (ketamine 80 mg/kg, xylazine 8 mg/kg, i.p.) [18]. The nerve was separated and loosely ligated at four points (1 mm apart) using 4-0 chromic gut sutures without compromising blood flow. The muscle and skin were sutured, the site was disinfected, and covered with tetracycline ointment [19].

Preparation of Conditioned Medium (CM)

CM was derived from fourth-passage human amniotic MSCs. MSCs were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and other standard growth factors under normoxic conditions (37°C, 5% CO₂). After reaching 80%–90% confluence, the culture medium was replaced with serum-free DMEM, and the cells were incubated for an additional 7 days to allow secretion of bioactive factors. The supernatant was collected, centrifuged at 1600 rpm for 5 minutes to remove cellular debris, and passed through a 0.22-μm sterile filter to obtain the final CM [20].

Administration of Conditioned Medium (CM) or Vehicle

Thirty minutes post-CCI induction, 10 µL of CM was slowly injected into the sciatic nerve sheath proximal to the ligation site (near the fourth ligation point) over 2 minutes using a Hamilton syringe [17, 21]. The Vehicle group received an equivalent volume (10 µL) of plain DMEM administered similarly.

Behavioral Assessments of Pain

Pain-related behaviors were evaluated using the plantar test (for thermal hyperalgesia), acetone test (for cold allodynia), and Randall–Selitto test (for mechanical hyperalgesia) [16, 22]:

Plantar Test: Thermal hyperalgesia was assessed by measuring the latency to hind paw withdrawal from an infrared heat source. A cutoff time of 25 seconds was implemented to avoid tissue damage. Each rat was tested in three trials separated by 10-minute intervals, and the average latency was recorded [23].

Randall–Selitto Test: Mechanical hyperalgesia was quantified by applying incrementally increasing pressure to the hind paw until a withdrawal response was elicited. At least two trials per rat were conducted at 1-minute intervals, and the mean pressure threshold was calculated [24].

Acetone Test: Cold allodynia was evaluated by applying a single drop of acetone to the plantar surface of the hind paw. Behavioral responses (e.g., withdrawal, licking, or shaking) were scored over five trials, with 1-minute intervals between applications [25].

Assessment of Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) Expression by Western Blotting

CGRP expression in the lumbar spinal cord was analyzed using western blotting [26]. Rats were deeply anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg) intraperitoneally [27]. Following laminectomy, the lumbar spinal cord (L4–L6 segments) was excised, rinsed in ice-cold 0.1 M phosphate-buffered saline, and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen within 3 minutes to minimize protein degradation [28]. Samples were stored at –80°C until processing [29].

Tissues were homogenized in the Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act (RIPA) lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors [30]. Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Equal amounts of protein (30–50 µg) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride or polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes [31]. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween® 20 detergent (TBST) for 1 hour at room temperature, then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against CGRP (1:1000 dilution) and β-actin (1:5000, loading control) [32]. After washing, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000) for 1 hour [33]. Bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents and quantified by densitometry with ImageJ software. CGRP expression levels were normalized to β-actin [34].

Results

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometric analysis confirmed the mesenchymal nature of the cultured cells. Most (> 95%) cells expressed CD44, supporting their adhesive and migratory properties crucial for regenerative activity. CD45 was undetectable, indicating the absence of hematopoietic cells, while a subset of cells exhibited CD90 expression, consistent with stemness-related characteristics (Figure 1). These findings validated the cellular source of CM utilized in subsequent experiments.

Figure 1. Evaluation of Surface Marker Expression in Amniotic-derived Stem Cells by Flow Cytometry

Behavioral Tests

Randall's test indicated a decreased threshold for mechanical sensitivity in all groups subjected to chronic constriction injury (CCI) on the first day following the procedure. However, the results were not statistically significant. From day two to day 21, mechanical sensitivity progressively increased. A vital difference emerged by day seven between the CM and vehicle groups. Although sensitivity slightly declined in the treatment group by day 21, this reduction was not statistically significant, suggesting a potentially greater analgesic effect with extended observation (Figure 2).

Statistical analysis confirmed that CM-treated rats exhibited a significant increase in mechanical withdrawal thresholds compared to both CCI (*P < 0.05) and vehicle (**P < 0.01) groups from day seven onward (Figure 2).

Randall's test indicated a decreased threshold for mechanical sensitivity in all groups subjected to chronic constriction injury (CCI) on the first day following the procedure. However, the results were not statistically significant. From day two to day 21, mechanical sensitivity progressively increased. A vital difference emerged by day seven between the CM and vehicle groups. Although sensitivity slightly declined in the treatment group by day 21, this reduction was not statistically significant, suggesting a potentially greater analgesic effect with extended observation (Figure 2).

Statistical analysis confirmed that CM-treated rats exhibited a significant increase in mechanical withdrawal thresholds compared to both CCI (*P < 0.05) and vehicle (**P < 0.01) groups from day seven onward (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The Effect of Intrathecal Injection of Conditioned Media on Mechanical Sensitivity Threshold After Induction of Neuropathic Pain, Based on the Randall Behavioral Test. In all groups, the mechanical sensitivity threshold decreased after CCI induction. In rats receiving conditioned media, the reduction in sensitivity is significant compared to the CCI and Vehicle groups from the seventh day. Values are presented as mean ± SEM. Each group consisted of eight rats. * denotes a statistically significant difference relative to the Vehicle group (P < 0.01).

In the acetone test for cold sensitivity, a statistically significant reduction in threshold was observed across all CCI groups after injury (F [10] = 1.93, P = 0.047). No significant intergroup differences were observed on days one and three. By days seven and fourteen, pain responses escalated in intensity. However, the CM group exhibited significantly reduced pain compared to the vehicle group on day seven (P = 0.011) and the CCI group on day 14 (P = 0.011). By day 21, differences were not statistically significant (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Effect of Intrathecal Injection of Conditioned Media After the Induction of Neuropathic Pain on the Cold Stimulation Threshold Based on the Acetone Behavioral Test. In all groups, the cold stimulation threshold decreased after CCI induction. In rats receiving conditioned media, the reduction in stimulation threshold was significantly less compared to the CCI and Vehicle groups from day seven onwards. The results are expressed as mean ± SEM. Each experimental group included eight rats. An asterisk (*) denotes a statistically significant difference compared to the nerve injury group (P < 0.05). The symbol ($) indicates a substantial difference from the vehicle group (P < 0.05).

Assessment of Spinal Calcitonin Gene-related Peptide (CGRP) Protein Expression Post-nerve Injury

CGRP expression was evaluated via Western blotting using spinal cord samples collected at the study endpoint and stored at –80°C. Statistical analysis indicated significant differences in CGRP levels among the groups (df = 4; F = 12.83; P = 0.002). Expression was markedly reduced in the CM group (0.85 ± 0.07) compared to the nerve injury (1.65 ± 0.05) and vehicle groups (1.79 ± 0.07). Intrapreneurial administration of CM significantly suppressed CGRP expression versus the nerve injury (P = 0.009) and vehicle groups (P = 0.006). Furthermore, CGRP concentrations in the CCI, vehicle, and CM groups were significantly different from those in the control group (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 4).

CGRP expression was evaluated via Western blotting using spinal cord samples collected at the study endpoint and stored at –80°C. Statistical analysis indicated significant differences in CGRP levels among the groups (df = 4; F = 12.83; P = 0.002). Expression was markedly reduced in the CM group (0.85 ± 0.07) compared to the nerve injury (1.65 ± 0.05) and vehicle groups (1.79 ± 0.07). Intrapreneurial administration of CM significantly suppressed CGRP expression versus the nerve injury (P = 0.009) and vehicle groups (P = 0.006). Furthermore, CGRP concentrations in the CCI, vehicle, and CM groups were significantly different from those in the control group (P < 0.05, P < 0.001, and P < 0.001, respectively) (Figure 4).

Figure 1. The Expression Levels Of Spinal Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (Cgrp)/Β-Actin Protein Within The Spinal Cords Of Animals Across The Experimental Groups. Data are reported as mean ± Sem. ** Statistically significant difference in comparison to the cm group (p < 0.01)

### Significant difference compared to the control group (P < 0.05 and P < 0.001, respectively).

Discussion

Neuropathic pain, arising from peripheral or central nerve injuries, involves complex mechanisms such as neuronal apoptosis, neuroinflammation, and central sensitization, which collectively challenge effective therapeutic management [35]. Conventional treatments, including antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids, often yield limited and transient relief, underscoring the need for novel interventions [35]. The CCI model, a well-established preclinical paradigm, recapitulates key features of human neuropathic pain, including mechanical hyperalgesia, cold allodynia, and thermal hyperalgesia, thereby facilitating the evaluation of potential therapeutics [36].

This study investigated the therapeutic potential of CM derived from human amniotic MSCs in a CCI model. CM, comprising a rich secretome of bioactive factors, such as cytokines, growth factors (e.g., BDNF, NGF, VEGF), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and matrix proteins, offers regenerative and immunomodulatory benefits without the risks associated with direct cell transplantation, such as immune rejection or tumorigenicity [37, 38]. Our findings demonstrate that intrapreneurial CM administration significantly attenuates behavioral manifestations of neuropathic pain, including mechanical hyperalgesia and cold allodynia, while concurrently reducing spinal CGRP levels, a key mediator of nociceptive signaling.

Behavioral assessments revealed a progressive onset of neuropathic symptoms post-CCI, with peak hypersensitivity observed between days 7 and 14, consistent with the model's temporal profile of neuroinflammation and sensitization. CM treatment elicited significant improvements in mechanical withdrawal thresholds (Randall-Selitto test) from day 7 onward, with sustained effects until day 21, albeit without statistical significance at the latter time point. Similarly, in the acetone test, CM reduced cold allodynia responses on days 7 and 14 compared to CCI and vehicle controls. These temporal patterns suggest an early and robust analgesic effect of CM, potentially extending beyond the observation period, as indicated by the trend toward further improvement on day 21. Further studies could elucidate whether these benefits persist or require repeated dosing for chronic management.

Integrating these behavioral outcomes with biochemical findings, the marked reduction in spinal CGRP expression in the CM group (0.85 ± 0.07 vs. 1.65 ± 0.05 in the CCI group and 1.79 ± 0.07 in the vehicle group; P < 0.01) provides a mechanistic link to pain alleviation. CGRP, a 37-amino-acid neuropeptide existing in α and β isoforms, is predominantly expressed in C-fiber sensory neurons and dorsal root ganglia, where it co-localizes with substance P and modulates nociception through receptor activation (e.g., receptor-like receptor [CLR]/receptor activity-modulating proteins [RAMP1] complex) [39, 40]. In neuropathic states, elevated CGRP promotes neurogenic inflammation via peripheral vasodilation and immune cell recruitment, while centrally enhancing synaptic plasticity and sensitization in the spinal dorsal horn (laminae I, III, V) [41, 42]. The observed decrease in spinal CGRP directly correlates with diminished allodynia and hyperalgesia, as reduced CGRP signaling likely interrupts amplified nociceptive transmission and central hypersensitivity, elevating pain thresholds, as evidenced in our behavioral data.

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking CM to CGRP modulation and pain relief, we considered the multifaceted actions of the MSC secretome. CM's anti-inflammatory components, such as interleukin (IL)-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, IL-1β) released by activated microglia and astrocytes post-nerve injury, mitigating neuroinflammation that upregulates CGRP expression [43]. Additionally, neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) in CM, may promote neuronal survival and repair, preventing apoptosis and ectopic firing that exacerbate CGRP release [44]. Emerging evidence also implicates EVs within CM, which carry micro ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) (e.g., miR-101b-3p) capable of targeting pain-related channels, such as Nav1.6, or modulating CGRP pathways indirectly through anti-inflammatory effects (from recent studies on TNF-α-preconditioned MSC-EVs) [45]. Furthermore, CM may influence vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) signaling, a pathway implicated in MSC-mediated pain modulation, potentially reducing vascular permeability and neurogenic inflammation associated with CGRP [46]. These mechanisms collectively dampen the vicious cycle of inflammation-sensitization-pain, with CGRP downregulation as a downstream effector aligning with the observed behavioral improvements.

Comparing our results with prior studies reinforces the therapeutic promise of CM while highlighting nuances in source-specific efficacy. For instance, Gama et al. (2018) reported that bone marrow-derived MSC-CM produced long-lasting antinociception in a mouse CCI model, attributing effects to immunomodulation and reduced glial activation, akin to our findings but without CGRP assessment [38]. Similarly, Masoodifar et al. (2021) demonstrated that MSC-CM reduced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathic rats by downregulating P2X4/P2X7 purinergic receptors in the spinal cord, suggesting overlapping pathways with CGRP modulation, as purinergic signaling intersects with neuropeptide release [39]. In a partial sciatic nerve ligation model, Jaleh et al. (2024) found that CM from dental pulp stem cells ameliorated pain behaviors, potentially via anti-apoptotic and regenerative effects, mirroring our behavioral outcomes but extending to longer durations (up to 28 days) [16]. Preemptive CM administration has also been shown to prevent pain development by attenuating early inflammation, as in a 2024 study, which aligns with our post-injury timing but suggests prophylactic potential [47]. Notably, our focus on amniotic MSC-CM and spinal CGRP distinguishes this study, as few studies link CM to CGRP specifically; however, indirect evidence from OA models indicates that MSC-derived EVs may target CGRP pathways [46]. Discrepancies, such as varying effect durations, may stem from CM source (amniotic vs. bone marrow/adipose), administration route (intrapreneurial vs. intravenous/intrathecal), or model specifics, warranting comparative trials.

Although CGRP antagonists (e.g., monoclonal antibodies) have shown variable efficacy in migraine and osteoarthritis (OA), with LY2951742 demonstrating limited success in mild OA due to baseline severity [48], CM offers a broader, multifaceted approach by targeting upstream inflammation and promoting regeneration. Limitations include the short-term observation and lack of direct EV or cytokine profiling in CM; future studies should incorporate these, alongside longer timelines and human translational models, to optimize CM for clinical use.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained from the investigation of pain-related behavioral tests and the effects of conditioned media, the specific characteristics of conditioned media led to a reduction in CGRP. Subsequently, the pain neuropathy sensitization threshold, which is elevated due to neuronal injury, is reduced, leading to decreased neuropathic pain levels in the group treated with conditioned media. Therefore, conditioned media, rich in various growth factors, neurotrophins, glucose, and amino acids holds significant potential for repairing and maintaining neurons. It can potentially improve inflammation and damage in neuropathic pain conditions in which neurons are compromised, thus proving highly effective in pain relief. Further extensive studies are required to confirm conditioned media as a suitable alternative to pain-relieving drugs in neuropathic pain conditions.

Ethical Considerations

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Approval Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.438). The experimental protocols were performed in full compliance with the established ethical standards. The Iran University of Medical Sciences provided institutional ethics oversight.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data produced or evaluated during this study are presented in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to everyone who contributed to this project, thereby advancing scientific knowledge. Their significant or minor efforts have enriched our insights and paved the way for future research.

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software: A.S, M.S., F.N; Data curation, writing-original draft preparation, and supervision: Z.J; Visualization, investigation: B.R.

Software, validation: Z.J; Writing-reviewing and editing: F.N., A.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/Support

No external funding or support was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

Neuropathic pain, arising from peripheral or central nerve injuries, involves complex mechanisms such as neuronal apoptosis, neuroinflammation, and central sensitization, which collectively challenge effective therapeutic management [35]. Conventional treatments, including antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and opioids, often yield limited and transient relief, underscoring the need for novel interventions [35]. The CCI model, a well-established preclinical paradigm, recapitulates key features of human neuropathic pain, including mechanical hyperalgesia, cold allodynia, and thermal hyperalgesia, thereby facilitating the evaluation of potential therapeutics [36].

This study investigated the therapeutic potential of CM derived from human amniotic MSCs in a CCI model. CM, comprising a rich secretome of bioactive factors, such as cytokines, growth factors (e.g., BDNF, NGF, VEGF), extracellular vesicles (EVs), and matrix proteins, offers regenerative and immunomodulatory benefits without the risks associated with direct cell transplantation, such as immune rejection or tumorigenicity [37, 38]. Our findings demonstrate that intrapreneurial CM administration significantly attenuates behavioral manifestations of neuropathic pain, including mechanical hyperalgesia and cold allodynia, while concurrently reducing spinal CGRP levels, a key mediator of nociceptive signaling.

Behavioral assessments revealed a progressive onset of neuropathic symptoms post-CCI, with peak hypersensitivity observed between days 7 and 14, consistent with the model's temporal profile of neuroinflammation and sensitization. CM treatment elicited significant improvements in mechanical withdrawal thresholds (Randall-Selitto test) from day 7 onward, with sustained effects until day 21, albeit without statistical significance at the latter time point. Similarly, in the acetone test, CM reduced cold allodynia responses on days 7 and 14 compared to CCI and vehicle controls. These temporal patterns suggest an early and robust analgesic effect of CM, potentially extending beyond the observation period, as indicated by the trend toward further improvement on day 21. Further studies could elucidate whether these benefits persist or require repeated dosing for chronic management.

Integrating these behavioral outcomes with biochemical findings, the marked reduction in spinal CGRP expression in the CM group (0.85 ± 0.07 vs. 1.65 ± 0.05 in the CCI group and 1.79 ± 0.07 in the vehicle group; P < 0.01) provides a mechanistic link to pain alleviation. CGRP, a 37-amino-acid neuropeptide existing in α and β isoforms, is predominantly expressed in C-fiber sensory neurons and dorsal root ganglia, where it co-localizes with substance P and modulates nociception through receptor activation (e.g., receptor-like receptor [CLR]/receptor activity-modulating proteins [RAMP1] complex) [39, 40]. In neuropathic states, elevated CGRP promotes neurogenic inflammation via peripheral vasodilation and immune cell recruitment, while centrally enhancing synaptic plasticity and sensitization in the spinal dorsal horn (laminae I, III, V) [41, 42]. The observed decrease in spinal CGRP directly correlates with diminished allodynia and hyperalgesia, as reduced CGRP signaling likely interrupts amplified nociceptive transmission and central hypersensitivity, elevating pain thresholds, as evidenced in our behavioral data.

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms linking CM to CGRP modulation and pain relief, we considered the multifaceted actions of the MSC secretome. CM's anti-inflammatory components, such as interleukin (IL)-10, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), suppress pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, IL-1β) released by activated microglia and astrocytes post-nerve injury, mitigating neuroinflammation that upregulates CGRP expression [43]. Additionally, neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and nerve growth factor (NGF) in CM, may promote neuronal survival and repair, preventing apoptosis and ectopic firing that exacerbate CGRP release [44]. Emerging evidence also implicates EVs within CM, which carry micro ribonucleic acids (miRNAs) (e.g., miR-101b-3p) capable of targeting pain-related channels, such as Nav1.6, or modulating CGRP pathways indirectly through anti-inflammatory effects (from recent studies on TNF-α-preconditioned MSC-EVs) [45]. Furthermore, CM may influence vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) signaling, a pathway implicated in MSC-mediated pain modulation, potentially reducing vascular permeability and neurogenic inflammation associated with CGRP [46]. These mechanisms collectively dampen the vicious cycle of inflammation-sensitization-pain, with CGRP downregulation as a downstream effector aligning with the observed behavioral improvements.

Comparing our results with prior studies reinforces the therapeutic promise of CM while highlighting nuances in source-specific efficacy. For instance, Gama et al. (2018) reported that bone marrow-derived MSC-CM produced long-lasting antinociception in a mouse CCI model, attributing effects to immunomodulation and reduced glial activation, akin to our findings but without CGRP assessment [38]. Similarly, Masoodifar et al. (2021) demonstrated that MSC-CM reduced mechanical allodynia and thermal hyperalgesia in neuropathic rats by downregulating P2X4/P2X7 purinergic receptors in the spinal cord, suggesting overlapping pathways with CGRP modulation, as purinergic signaling intersects with neuropeptide release [39]. In a partial sciatic nerve ligation model, Jaleh et al. (2024) found that CM from dental pulp stem cells ameliorated pain behaviors, potentially via anti-apoptotic and regenerative effects, mirroring our behavioral outcomes but extending to longer durations (up to 28 days) [16]. Preemptive CM administration has also been shown to prevent pain development by attenuating early inflammation, as in a 2024 study, which aligns with our post-injury timing but suggests prophylactic potential [47]. Notably, our focus on amniotic MSC-CM and spinal CGRP distinguishes this study, as few studies link CM to CGRP specifically; however, indirect evidence from OA models indicates that MSC-derived EVs may target CGRP pathways [46]. Discrepancies, such as varying effect durations, may stem from CM source (amniotic vs. bone marrow/adipose), administration route (intrapreneurial vs. intravenous/intrathecal), or model specifics, warranting comparative trials.

Although CGRP antagonists (e.g., monoclonal antibodies) have shown variable efficacy in migraine and osteoarthritis (OA), with LY2951742 demonstrating limited success in mild OA due to baseline severity [48], CM offers a broader, multifaceted approach by targeting upstream inflammation and promoting regeneration. Limitations include the short-term observation and lack of direct EV or cytokine profiling in CM; future studies should incorporate these, alongside longer timelines and human translational models, to optimize CM for clinical use.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained from the investigation of pain-related behavioral tests and the effects of conditioned media, the specific characteristics of conditioned media led to a reduction in CGRP. Subsequently, the pain neuropathy sensitization threshold, which is elevated due to neuronal injury, is reduced, leading to decreased neuropathic pain levels in the group treated with conditioned media. Therefore, conditioned media, rich in various growth factors, neurotrophins, glucose, and amino acids holds significant potential for repairing and maintaining neurons. It can potentially improve inflammation and damage in neuropathic pain conditions in which neurons are compromised, thus proving highly effective in pain relief. Further extensive studies are required to confirm conditioned media as a suitable alternative to pain-relieving drugs in neuropathic pain conditions.

Ethical Considerations

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Iran University of Medical Sciences (Approval Code: IR.IUMS.FMD.REC.1400.438). The experimental protocols were performed in full compliance with the established ethical standards. The Iran University of Medical Sciences provided institutional ethics oversight.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data produced or evaluated during this study are presented in this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their gratitude to everyone who contributed to this project, thereby advancing scientific knowledge. Their significant or minor efforts have enriched our insights and paved the way for future research.

Authors' Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software: A.S, M.S., F.N; Data curation, writing-original draft preparation, and supervision: Z.J; Visualization, investigation: B.R.

Software, validation: Z.J; Writing-reviewing and editing: F.N., A.S. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding/Support

No external funding or support was received for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

References

- Scholz J, Finnerup NB, Attal N, Aziz Q, Baron R, Bennett MI, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic neuropathic pain. Pain. 2019 ;l160(1) : 53-59. [DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001365]

- Ji RR, Nackley A, Huh Y, Terrando N, Maixner W. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(2):343-366. [DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002130]

- Kiabi FH, Khosravi T, Ahangar SG, Beiranvand S. The importance of stem cells in the treatment of neuropathic pain. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2025;25(4):427-436. [DOI: 10.2174/0118715249328823241111101137]

- Jiang L, Jones S, Jia X. Stem cell transplantation for peripheral nerve regeneration: current options and opportunities. Int J Mol Sci. 2017 Jan 5;18(1):94. [DOI: 10.3390/ijms18010094]

- Fonseca LN, Bolívar-Moná S, Agudelo T, Beltrán LD, Camargo D, Correa N, et al. Cell surface markers for mesenchymal stem cells related to the skeletal system: A scoping review. Heliyon. 2023;9(2):e13464. [DOI: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e13464]

- Sawada R, Nakano-Doi A, Matsuyama T, Nakagomi N, Nakagomi T. CD44 expression in stem cells and niche microglia/macrophages following ischemic stroke. Stem Cell Investig. 2020;7:4. [DOI: 10.21037/sci.2020.02.02]

- Muñiz C, Teodosio C, Mayado A, Amaral AT, Matarraz S, Bárcena P, et al. Ex vivo identification and characterization of a population of CD13(high) CD105(+) CD45(-) mesenchymal stem cells in human bone marrow. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2015;6(1):169. [DOI: 10.1186/s13287-015-0152-8] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Chouaib B, Haack-Sørensen M, Chaubron F, Cuisinier F, Collart-Dutilleul PY. Towards the standardization of mesenchymal stem cell secretome-derived product manufacturing for tissue regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(16):12594. [DOI: 10.3390/ijms241612594] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Sriramulu S, Banerjee A, Di Liddo R, Jothimani G, Gopinath M, Murugesan R, et al. Concise review on clinical applications of conditioned medium derived from human umbilical cord-mesenchymal stem cells (UC-MSCs). Int J Hematol Oncol Stem Cell Res. 2018;12(3):230-234. [PMID] [PMCID]

- El Moshy S, Radwan IA, Rady D, Abbass MMS, El-Rashidy AA, Sadek KM, et al. Dental stem cell-derived secretome/conditioned medium: the future for regenerative therapeutic applications. Stem Cells Int. 2020 ;2020:7593402. [DOI: 10.1155/2020/7593402]

- Müller P, Lemcke H, David R. Stem cell therapy in heart diseases - cell types, mechanisms and improvement strategies. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48(6):2607-2655. [DOI: 10.1159/000492704]

- An Q, Sun C, Li R, Chen S, Gu X, An S, Wang Z. Calcitonin gene-related peptide regulates spinal microglial activation through the histone H3 lysine 27 trimethylation via enhancer of zeste homolog-2 in rats with neuropathic pain. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18(1):117. [DOI: 10.1186/s12974-021-02168-1] [PMID]

- Iyengar S, Ossipov MH, Johnson KW. The role of calcitonin gene-related peptide in peripheral and central pain mechanisms including migraine. Pain. 2017;158(4):543-559. [DOI: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000831] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Liu Y, Kano F, Hashimoto N, Xia L, Zhou Q, Feng X, et al. Conditioned medium from the stem cells of human exfoliated deciduous teeth ameliorates neuropathic pain in a partial sciatic nerve ligation model. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:745020. [DOI: 10.3389/fphar.2022.745020] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Lale Ataei M, Karimipour M, Shahabi P, Pashaei-Asl R, Ebrahimie E, Pashaiasl M. The restorative effect of human amniotic fluid stem cells on spinal cord injury. Cells. 2021;10(10):2565. [DOI: 10.3390/cells10102565]

- Jaleh Z, Rahimi B, Shahrezaei A, Sohani M, Sagen J, Nasirinezhad F. Exploring the therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem cells-derived conditioned medium: an in-depth analysis of pain alleviation, spinal ccl2 levels, and oxidative stress. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2024;82(3):2977-2988. [DOI: 10.1007/s12013-024-01410-w]

- Wong CE, Hu CY, Lee PH, Huang CC, Huang HW, Huang CY, et al. Sciatic nerve stimulation alleviates acute neuropathic pain via modulation of neuroinflammation and descending pain inhibition in a rodent model. J Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):153. [DOI: 10.1186/s12974-022-02513-y] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Giroux MC, Hélie P, Burns P, Vachon P. Anesthetic and pathological changes following high doses of ketamine and xylazine in Sprague Dawley rats. Exp Anim. 2015;64(3):253-260. [DOI: 10.1538/expanim.14-0088] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Korah HE, Cheng K, Washington SM, Flowers ME, Stratton HJ, Patwardhan A, et al. Partial sciatic nerve ligation: a mouse model of chronic neuropathic pain to study the antinociceptive effect of novel therapies. J Vis Exp. 2022;(188). [DOI: 10.3791/64555]

- Takamura M, Zhou W, Rombauts L, Dimitriadis E. The long noncoding RNA PTENP1 regulates human endometrial epithelial adhesive capacity in vitro: implications in infertility. Biol Reprod. 2020;102(1):53-62. [DOI: 10.1093/biolre/ioz173]

- Sivanarayanan TB, Bhat IA, Sharun K, Palakkara S, Singh R, Remya 5th, et al. Allogenic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells and its conditioned media for repairing acute and sub-acute peripheral nerve injuries in a rabbit model. Tissue Cell. 2023;82:102053. [DOI: 10.1016/j.tice.2023.102053]

- Yam MF, Loh YC, Oo CW, Basir R. Overview of neurological mechanism of pain profile used for animal "pain-like" behavioral study with proposed analgesic pathways. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(12):4355. [DOI:10.3390/ijms21124355]

- Leite-Panissi CRA, De Paula BB, Neubert JK, Caudle RM. Influence of TRPV1 on thermal nociception in rats with temporomandibular joint persistent inflammation evaluated by the operant orofacial pain assessment device (OPAD). J Pain Res. 2023;16:2047-2062. [DOI: 10.2147/JPR.S405258] [PMID]

- Oliveria JC, Silva DPB, Florentino IF, da Silva LC, Sanz G, Vaz BG, et al. Design, synthesis and pharmacological assessment of new pyrazole compounds. Inflammopharmacology. 2020;28(4):915-928. [DOI: 10.1007/s10787-020-00727-1]

- Hubbard CS, Khan SA, Xu S, Cha M, Masri R, Seminowicz DA. Behavioral, metabolic and functional brain changes in a rat model of chronic neuropathic pain: a longitudinal MRI study. Neuroimage. 2015;107:333-344. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.12.024]

- Reducha PV, Bömers JP, Edvinsson L, Haanes KA. The impact of the migraine treatment onabotulinumtoxinA on inflammatory and pain responses: Insights from an animal model. Headache. 2024;64(6):652-662. [DOI: 10.1111/head.14726]

- Tsuji Y. Transmembrane protein western blotting: Impact of sample preparation on detection of SLC11A2 (DMT1) and SLC40A1 (ferroportin). PLoS One. 2020;15(7):e0235563. [DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235563] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Garić D, Dumut DC, Centorame A, Radzioch D. Western blotting with fast SDS-PAGE and semi-dry protein transfer. Curr Protoc. 2023;3(7):e833. [DOI: 10.1002/cpz1.833]

- Wirths O. Extraction of soluble and insoluble protein fractions from mouse brains and spinal cords. Bio Protoc. 2017;7(15):e2422. [DOI: 10.21769/BioProtoc.2422] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Miskiewicz EI, MacPhee DJ. Lysis buffer choices are key considerations to ensure effective sample solubilization for protein electrophoresis. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1855:61-72. [DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8793-1_5]

- Bainor A, Chang L, McQuade TJ, Webb B, Gestwicki JE. Bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay in low volume. Anal Biochem. 2011;410(2):310-312. [DOI: 10.1016/j.ab.2010.11.015]

- Edvinsson L, Grell AS, Warfvinge K. Expression of the CGRP family of neuropeptides and their receptors in the trigeminal ganglion. J Mol Neurosci. 2020;70(6):930-944. [DOI: 10.1007/s12031-020-01493-z]

- Kielkopf CL, Bauer W, Urbatsch IL. Analysis of proteins by immunoblotting. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2021;2021(12). [DOI: 10.1101/pdb.prot102251]

- Gárate G, Pascual J, Pascual-Mato M, Madera J, Martín MM, González-Quintanilla V. Untangling the mess of CGRP levels as a migraine biomarker: an in-depth literature review and analysis of our experimental experience. J Headache Pain. 2024;25(1):69. [DOI: 10.1186/s10194-024-01769-4]

- Fernandes V, Sharma D, Vaidya S, PA S, Guan Y, Kalia K, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms driving neuropathic pain: recent advancements and challenges. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2018;22(2):131-142. [DOI: 10.1080/14728222.2018.1420781]

- Wilkerson JL, Jiang J, Felix JS, Bray JK, da Silva L, Gharaibeh RZ, et al. Alterations in mouse spinal cord and sciatic nerve microRNAs after the chronic constriction injury (CCI) model of neuropathic pain. Neurosci Lett. 2020;731. [DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2020.135029]

- Qi L, Wang R, Shi Q, Yuan M, Jin M, Li D. Umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cell conditioned medium restored the expression of collagen II and aggrecan in nucleus pulposus mesenchymal stem cells exposed to high glucose. J Bone Miner Metab. 2019;37(3):455-466. [DOI: 10.1007/s00774-018-0953-9]

- Gama KB, Santos DS, Evangelista AF, Silva DN, de Alcântara AC, Dos Santos RR, et al. Conditioned medium of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells as a therapeutic approach to neuropathic pain: a preclinical evaluation. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:8179013. [DOI: 10.1155/2018/8179013]

- Masoodifar M, Hajihashemi S, Pazhoohan S, Nazemi S, Mojadadi MS. Effect of the conditioned medium of mesenchymal stem cells on the expression levels of P2X4 and P2X7 purinergic receptors in the spinal cord of rats with neuropathic pain. Purinergic Signal. 2021;17(1):143-150. [DOI: 10.1007/s11302-020-09756-5] [PMID]

- Kee Z, Kodji X, Brain SD. The Role of calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) in neurogenic vasodilation and its cardioprotective effects. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1249. [DOI: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01249] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Rubio-Beltran E, Chan KY, Danser AJ, MaassenVanDenBrink A, Edvinsson L. Characterisation of the calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonists ubrogepant and atogepant in human isolated coronary, cerebral and middle meningeal arteries. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(4):357-366. [DOI: 10.1177/0333102419884943]

- Imran A, Xiao L, Ahmad W, Anwar H, Rasul A, Imran M, et al. Foeniculum vulgare (Fennel) promotes functional recovery and ameliorates oxidative stress following a lesion to the sciatic nerve in mouse model. J Food Biochem. 2019;43(9):e12983. [DOI: 10.1111/jfbc.12983]

- González-Cubero E, González-Fernández ML, Olivera ER, Villar-Suárez V. Extracellular vesicle and soluble fractions of adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells secretome induce inflammatory cytokines modulation in an in vitro model of discogenic pain. Spine J. 2022;22(7):1222-1234. [DOI: 10.1016/j.spinee.2022.01.012]

- Belinskaia M, Zurawski T, Kaza SK, Antoniazzi C, Dolly JO, Lawrence GW. NGF enhances CGRP release evoked by capsaicin from rat trigeminal neurons: differential inhibition by SNAP-25-cleaving proteases. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(2):892. [DOI: 10.3390/ijms23020892] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Zhang L, Wang J, Liu J, Xin J, Tan Y, Zhang D, et al. TNF-α-preconditioning enhances analgesic efficacy of mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicle in neuropathic pain via miR-101b-3p targeting Nav1.6. Bioact Mater. 2025;53:522-539. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bioactmat.2025.07.029] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Liebmann K, Castillo MA, Jergova S, Best TM, Sagen J, Kouroupis D. Modification of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-derived small extracellular vesicles by calcitonin gene related peptide (CGRP) antagonist: potential implications for inflammation and pain reversal. Cells. 2024;13(6):484. [DOI: 10.3390/cells13060484] [PMID] [PMCID]

- Nazemi S, Helmi M, Kafami M, Amin B, Mojadadi MS. Preemptive administration of mesenchymal stem cells-derived conditioned medium can attenuate the development of neuropathic pain in rats via downregulation of proinflammatory cytokines. Behav Brain Res. 2024 ;461:114858. [DOI: 10.1016/j.bbr.2024.114858]

- Sánchez-Rodríguez C, Gago-Veiga AB, García-Azorín D, Guerrero-Peral ÁL, Gonzalez-Martinez A. Potential predictors of response to CGRP monoclonal antibodies in chronic migraine: real-world data. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2024;28(12):1265-1272. [DOI: 10.1007/s11916-023-01183-6] [PMID]

Article Type: Research Article |

Subject:

Physiology

Received: 2025/07/8 | Accepted: 2025/09/8 | Published: 2025/09/25

Received: 2025/07/8 | Accepted: 2025/09/8 | Published: 2025/09/25

Send email to the article author

| Rights and permissions | |

|

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. |